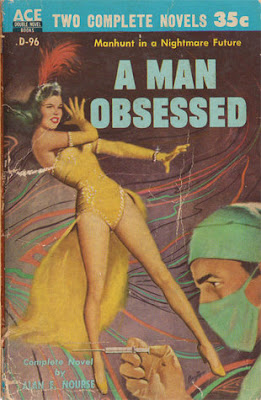

"A Man Obsessed" aka "The Mercy Men" by Alan E. Nourse

Alan E. Nourse’s The Mercy Men (1955) contains all the necessary parts for a riveting 1950s SF thriller: a disturbing future America where the destitute sell their bodies for medical experimentation, a world wrecked by increasing waves of mental illness, and a hero with a manic obsession with finding the man who killed his father. However, Nourse’s strategic dousing of the characters and scenes with Extra Sensory Perception (ESP) hoopla muddles the wonder of the world and rigor of the action and leaves the reader imagining all the lost opportunities.

Alan E. Nourse’s The Mercy Men (1955) contains all the necessary parts for a riveting 1950s SF thriller: a disturbing future America where the destitute sell their bodies for medical experimentation, a world wrecked by increasing waves of mental illness, and a hero with a manic obsession with finding the man who killed his father. However, Nourse’s strategic dousing of the characters and scenes with Extra Sensory Perception (ESP) hoopla muddles the wonder of the world and rigor of the action and leaves the reader imagining all the lost opportunities.

And of course in the best pulp tradition which Nourse so fervently adheres to, science wins out in the end and provides nicely packaged easy answers. Outside of the occasional threadbare tangents evoking the world onto which the standard plot is grafted, The Mercy Men contains startling little substance despite the serious subject material. One would imagine a novel depicting “epidemics” of mental illness, a dystopic government situation where all the money is funneled into treatment, and the almost catastrophic societal strains would delve in a more sophisticated and evocative way into the forces at play…

In an America recovering from the effects of nuclear bombing and neurotoxic virus plagues a new challenge arises — “epidemics” of mental illness that result in additional societal instability. Because of the dangers if the “epidemic” goes unchecked, the government begins to pour money into giant hospital complexes which are tasked with investigating “the creeping illness” and “find [ing[ a out how to stop it”. Because the doctors at the Hoffman Center (the largest and most central of the medical complexes) have “learned all [they] can learn […] from studying cats and dogs and monkeys” human subjects for medical experiments were deemed necessary.

Desperate men and women, families wrecked by the manifold disasters or alcoholism etc, signed up at the Hoffman Center to be test subjects — nicknamed the titular Mercy Men. Because the tests could be incredibly dangerous giant payouts were promised for those who survived. Only those who were so desperate that they were willing to risk death were enrolled. Eventually the program was banned by law. However, despite the ban there are rumors that the Mercy Men still exist — but rather than being tested for cures of virulent diseases and plagues they allow their minds to be probed (and often destroyed) in order for “cures” to be found for mental illness.

However, all this research into the mind might have other “benefits” — “Scientists have been trying to document it for centuries, and they’ve never succeeded. Nobody’s ever proved that psychokinesis or other extra sensory powers even exist”.

Jeff Meyer left college and began to pursue with almost manic vigor the man who killed his statistician/scientist father — Conroe. But Conroe seems to mysteriously slip away whenever Meyer sets an elaborate trap. In one of these instances at the beginning of the novel Conroe escapes into the Hoffman Center. Jeff Meyer, throwing caution to the wind, enters the center in an effort to find Conroe and joins the Mercy Men — who are indeed still in existence. He soon discovers, along with other members of the Mercy Men, that he has unusual powers…. Perhaps that’s why he was lured into the Hoffman Center!

The novel reads like the dismal Hollywood adaption Impostor (2001) (with Vincent D’Onofrio, Gary Sinise, Madeleine Stowe) of Philip K. Dick’s harrowing short story “Impostor” (1953) — all empty action and no substance despite the intriguing premise. Also, there are very startling moral implications of how the plot’s finally resolved — human experimentation is strangely justified in Nourse’s eyes. Considering what else was published in that era, some might applaud Nourse for tackling these themes. My response is straightforward, the themes are present but never addressed in any meaningful way.

An opportunity lost — avoid.

Comments

Post a Comment