"The Space-Born" by E.C. Tubb

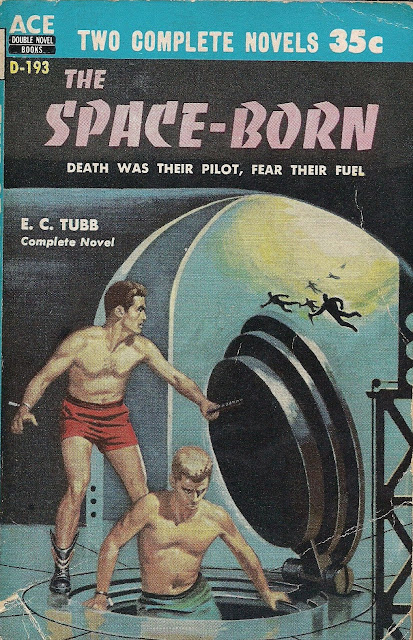

Almost the surprise of the year! E. C. Tubb’s The Space-Born (variant title: Star Ship) (1955) first appeared as a serial in New Worlds (April, May, and June 1955 issues). For American audiences, Tubb’s novel was paired with Philip K. Dick’s The Man Who Japed (1956) as an Ace Double. My only previous exposure to the prolific British author’s SF was “The Seekers” (1965), a paranoid vision of spacemen possessed by delusions of grandeur after their captain’s death. The Space-Born is a fascinating generation ship novel with a catastrophic flaw.

While a routine adventure story at heart, The Space-Born presents a disturbing dystopic vision of life on a generation ship. The physical space of the vessel—enclosed, controlled, inescapable—creates a regime that enforces stability through diabolical means (eugenics, forced sterilization, assassination of all over 40). Unfortunately, in the last few pages of the novel Tubb seems content celebrating the dystopia as a necessary evil to achieve humanity’s ultimate dream—spreading its tentacles across new planets… Imagine if Orwell’s 1984 (1949) occurred on a spaceship—and in the last few pages an alternate ending was tacked on: “the dystopia was necessary to achieve humanity’s dreams!” Tubb doesn’t seem to realize the fascist ideology his story endorses. Considering his output, he probably cranked this novel out at breakneck speed.

This is a fast and engaging read with fascinating societal details. I recommend the novel for completest fans of generation ships as its the perfect theme to explore repressive regimes. However, in the last four pages Tubb loses control of his narrative and ends up endorsing the dystopia he so carefully explores. A forced happy ending with horrific implications!

The Ship heads to Pollux, thirty-two light years from Earth. Three hundred years into its voyage, a repressive regime controlled by a central computer dictates every detail of one’s life. Women are forced into marriages between 18-24 years of age. At 25, they are sterilized and able to engage in whatever sexual relationships they desire. The focus on childbirth indicates the entire voyage is a eugenics experiment. All the unfit are disposed of by the secret police:

“Unfit meaning any and everyone who was not wholly capable of doing their job; the ill; the diseased; the barren; the unfertile; the neurotic; those that ate too much, who had slow reflexes, who were physically below par, who were mentally unstable. The unnecessary, the unessential, the old. Especially the old. For someone had to make room for the new generation”

Jay West, a member of the police force tasked with assassinating all crewmen over the age of 40, must confront his indoctrination when faced with the order to kill the father of his love interest, Susan. The hierarchy, i.e. the leaders of the police, genetics, and other departments must confront their impending 40-year birthdays and plot to stay alive. Meanwhile, a handful of “Barbs” (barbarians) have escaped into the No-Weight areas of the ship to avoid extermination. Jay and “Barbs” paths meet and the future of the ship is at stake!

Tubb successfully integrates a plethora of fascinating slice-of-life details while maintaining a fast-paced adventure story. While other authors imply the presence of indoctrination, Tubb explains the how: every person is required to fulfill an “educational film quota” or risk a downgrade in housing and status. At various points in the voyage, the ship’s computer will modulate the educational programs piped into all crew quarters. Slight changes in the types of programs—from pastoral scenes of Earth life to images of the elderly the butchering of animals–ramps up the tension as the novel unfolds.

Another common denominator of most generation ship stories is social stratification based on trade—authors assume a medieval guild-like structure will enable stability on long voyages.* In this dystopia, a mere glance at a crewmen indicates their position in society (see the multi-colored shorts in the Ace Double edition above) and success in duels. Identify cards contain all the genetic and psychological details collated by the central computer. Other brilliant slice-of-life details included by Tubb include vibrations that resonate throughout the ship:

“Against [Jay’s] shoulder he could feel the slight, never-ending vibrations of voices and musics, the susurration of engines and the countless sounds of everyday life, all caught and carried by the eternal metal, all mingling and travelling until damped out by fresher, newer sounds. A philosopher had once called the vibration the life-sound of the Ship; while it could be heard all was well, without it nothing could be right”

Touches like these create the feel that The Ship is a lived-in space rather than a bland series of hallways.

The last four pages drop the rating from “Good” to “Bad.” Rather than reflect on the moral implications of the indoctrinated who are subjected to the generational trauma of the 300-year voyage, Tubb’s all-too-simple ending ties up all the loose threads with a complete tonal shift that celebrates the carnage. In Tubb’s view a brutal dystopia based on eugenics and Stalinist purges of non-conformists and the “elderly” is a necessary evil in the quest to colonize the stars.

~

Note: I disagree with this common conclusion. Discontent in a small enclosed space would have serious consequences. Freedom to choose one’s path might yield the least resistance. Life on a generation ship should mimic life in a “free” society on Earth. The arts, philosophy, etc. should be encouraged—life should feel meaningful. If Journey’s End is the only goal then yes, the intermediary generations might feel as if they’re trapped in purgatory. If Journey’s End isn’t the sole purpose then the intermediary generations would find fulfillment in other ways. I’m still waiting for an author from this period to endorse such a position! (Joachim Boaz, Science Fiction Ruminations)

While a routine adventure story at heart, The Space-Born presents a disturbing dystopic vision of life on a generation ship. The physical space of the vessel—enclosed, controlled, inescapable—creates a regime that enforces stability through diabolical means (eugenics, forced sterilization, assassination of all over 40). Unfortunately, in the last few pages of the novel Tubb seems content celebrating the dystopia as a necessary evil to achieve humanity’s ultimate dream—spreading its tentacles across new planets… Imagine if Orwell’s 1984 (1949) occurred on a spaceship—and in the last few pages an alternate ending was tacked on: “the dystopia was necessary to achieve humanity’s dreams!” Tubb doesn’t seem to realize the fascist ideology his story endorses. Considering his output, he probably cranked this novel out at breakneck speed.

This is a fast and engaging read with fascinating societal details. I recommend the novel for completest fans of generation ships as its the perfect theme to explore repressive regimes. However, in the last four pages Tubb loses control of his narrative and ends up endorsing the dystopia he so carefully explores. A forced happy ending with horrific implications!

The Ship heads to Pollux, thirty-two light years from Earth. Three hundred years into its voyage, a repressive regime controlled by a central computer dictates every detail of one’s life. Women are forced into marriages between 18-24 years of age. At 25, they are sterilized and able to engage in whatever sexual relationships they desire. The focus on childbirth indicates the entire voyage is a eugenics experiment. All the unfit are disposed of by the secret police:

“Unfit meaning any and everyone who was not wholly capable of doing their job; the ill; the diseased; the barren; the unfertile; the neurotic; those that ate too much, who had slow reflexes, who were physically below par, who were mentally unstable. The unnecessary, the unessential, the old. Especially the old. For someone had to make room for the new generation”

Jay West, a member of the police force tasked with assassinating all crewmen over the age of 40, must confront his indoctrination when faced with the order to kill the father of his love interest, Susan. The hierarchy, i.e. the leaders of the police, genetics, and other departments must confront their impending 40-year birthdays and plot to stay alive. Meanwhile, a handful of “Barbs” (barbarians) have escaped into the No-Weight areas of the ship to avoid extermination. Jay and “Barbs” paths meet and the future of the ship is at stake!

Tubb successfully integrates a plethora of fascinating slice-of-life details while maintaining a fast-paced adventure story. While other authors imply the presence of indoctrination, Tubb explains the how: every person is required to fulfill an “educational film quota” or risk a downgrade in housing and status. At various points in the voyage, the ship’s computer will modulate the educational programs piped into all crew quarters. Slight changes in the types of programs—from pastoral scenes of Earth life to images of the elderly the butchering of animals–ramps up the tension as the novel unfolds.

Another common denominator of most generation ship stories is social stratification based on trade—authors assume a medieval guild-like structure will enable stability on long voyages.* In this dystopia, a mere glance at a crewmen indicates their position in society (see the multi-colored shorts in the Ace Double edition above) and success in duels. Identify cards contain all the genetic and psychological details collated by the central computer. Other brilliant slice-of-life details included by Tubb include vibrations that resonate throughout the ship:

“Against [Jay’s] shoulder he could feel the slight, never-ending vibrations of voices and musics, the susurration of engines and the countless sounds of everyday life, all caught and carried by the eternal metal, all mingling and travelling until damped out by fresher, newer sounds. A philosopher had once called the vibration the life-sound of the Ship; while it could be heard all was well, without it nothing could be right”

Touches like these create the feel that The Ship is a lived-in space rather than a bland series of hallways.

The last four pages drop the rating from “Good” to “Bad.” Rather than reflect on the moral implications of the indoctrinated who are subjected to the generational trauma of the 300-year voyage, Tubb’s all-too-simple ending ties up all the loose threads with a complete tonal shift that celebrates the carnage. In Tubb’s view a brutal dystopia based on eugenics and Stalinist purges of non-conformists and the “elderly” is a necessary evil in the quest to colonize the stars.

~

Note: I disagree with this common conclusion. Discontent in a small enclosed space would have serious consequences. Freedom to choose one’s path might yield the least resistance. Life on a generation ship should mimic life in a “free” society on Earth. The arts, philosophy, etc. should be encouraged—life should feel meaningful. If Journey’s End is the only goal then yes, the intermediary generations might feel as if they’re trapped in purgatory. If Journey’s End isn’t the sole purpose then the intermediary generations would find fulfillment in other ways. I’m still waiting for an author from this period to endorse such a position! (Joachim Boaz, Science Fiction Ruminations)

Comments

Post a Comment