"City At World's End" by Edmond Hamilton

Written near the dawn of the Cold War era and soon after mankind first became

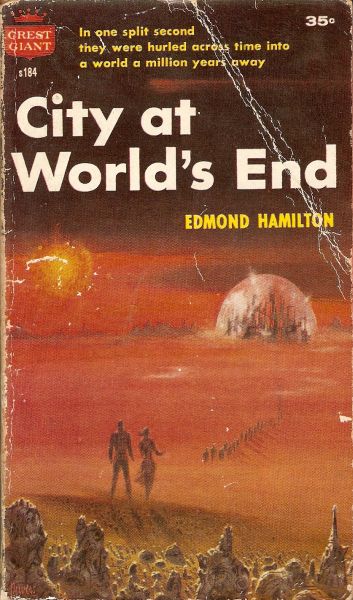

aware of the fearful possibilities of the atom bomb, City at World’s End yet remains both highly readable and grippingly entertaining today, more than 65 years after its initial appearance. Edmond Hamilton’s book initially as a “complete novel” in the July 1950 issue of the pulp magazine Starling Stories, was released in hardcover the following year, and, in ’53, appeared again in the pages of Galaxy. (Personally, I just finished reading the 35-cent Crest Giant paperback from 1957.) Hamilton, who was already 46 when he wrote this tale, had been a published author since 1926, and already had countless hundreds of short stories, novellas and novels under his spacebelt (I invite you to look up his bibliography online, such as on the Internet Speculative Database; you will be flabbergasted, trust me!) before he penned this 1950 affair. His marriage to the so-called “Queen of Space Opera,” Leigh Brackett, in 1946, only served to polish and refine his authorial technique, by his own admission. Thus, with the benefit of almost 25 years’ worth of unremitting practice and the input of what Hamilton later called his “kindest of critics,” the pulpmaster was able to come up with a genuinely well-written winner.

The novel strains the reader’s credulity in its opening pages, but if you can get past them alright, and buy into the central premise, you’ll be home free. In City at World’s End, the reader is introduced to the small city of Middletown, in Anywhere, U.S.A.; a burg of some 50,000 souls going about its business on a beautiful June morning. What the citizens of Middletown don’t know, however, is that its local industrial laboratory is actually the secret working site of a group of atomic physicists, which makes the otherwise undistinguished locale a prime target in a potential war. And before the citizenry is even aware of it, a so-called “super atomic” is exploded right over their heads, knocking one and all off their feet. And that’s all! As the populace dusts itself off, it is noticed that the air is now very much colder, and that the sun has changed to a gloomy-looking red ball in the heavens. The moon is now enormous, the stars are visible in the daytime sky, and the lab scientists, by analyzing those changed star patterns, soon come to realize the impossible truth: The city of Middletown has somehow been blown, via a rift in the time-space continuum, millions of years into Earth’s future!

In the book’s first section, Dr. John Kenniston and fellow physicist Hubble explore their devastated surroundings, only to discover an abandoned city protected by a hemispherical dome. As a means of sheltering themselves from the killing cold, an organized migration is effected, relocating the 50,000 Middletowners into the abandoned metropolis, which is dubbed New Middletown. In the book’s next section, men from outer space, representing the League of Stars, arrive near New Middletown in response to its radioed pleas for assistance; these Earthmen of the future and their alien shipmates help get New Middletown going but then insist on evacuating the 20th century community to another, more livable world, much against the wishes of the old-fashioned folk. Thus, in City at World’s End’s next section, it is up to Kenniston, as the city’s representative, to go to the galaxy’s capital world near Vega and plead his neighbors’ case before the Board of Governors. And before he knows it, he has also become embroiled in a plot involving the futuristic scientist Jon Arnol, who claims to have invented an “energy bomb” that can revive a dying planet…

Writing in his Ultimate Guide to Science Fiction, Scottish critic David Pringle says of Hamilton’s book that it is “an exciting tale full of standard space-opera elements — old-fashioned, implausible but full of pulp verve,” and I suppose that this is absolutely so. As for me, I really did enjoy Hamilton’s work here. City at World’s End contains that elusive “sense of wonder” that was held at such a high premium in Golden Age sci-fi. That sense of wonder is never more apparent than when Kenniston first gazes at the stars of deep space from the spaceship Thanis (“It was one thing to read and talk and speculate on flying space. It was another and much more frightening thing to do it, to step off the solid Earth, to rush and plunge and fall through the worldless emptiness…”), and when he first steps foot on the Vegan capital world. But Hamilton also manages to communicate that cosmic spirit of awe when the abandoned city under the dome is first explored (in a scene strangely reminiscent of the investigation of the domed alien city in Wylie & Balmer’s 1935 classic After Worlds Collide), and when the Middletowners espy their first nonhuman aliens (although the bearlike Gorr Holl from Capella and the catlike Magro from Spica ultimately become fast friends and allies of Kenniston).

Hamilton, who over the course of his Golden Age career had destroyed so many planets in his stories that he soon acquired the nickname “The World Wrecker” for himself, here shows an interest in figuring out a way to save a moribund Earth that is in its final death throes, and Arnol’s gizmo for doing so is a fascinating one. The author intersperses other surprising twists into his novel, as well. For example, Kenniston’s relationships with his girlfriend, Carol, and with the female alien administrator from Vega, Varn Allan, do not take the paths that the reader might expect. The people of Earth, rather than leaping at the chance to be rescued and to zoom off to a greener, warmer planet picked out especially for them, instead opt to stay on their dying homeworld. The children of Middletown, instead of being scared and intimidated by the imposing nonhumans, are the first to (literally) embrace them. Piers Eglin, the kindly Vegan historian, ultimately reveals himself to be something of a weasel. Bertram Garris, the pudgy, cowardly and often quite foolish mayor of Middletown, is later shown capable of some distinct leadership abilities, while the ultracool and capable Varn is shown to have some unsuspected depths. As does Kenniston himself at one point, quoting from Herman Melville’s third novel, 1849’s Mardi, by heart.

Hamilton’s writing style here, as always, is simple yet effective; a highly readable style that sweeps the reader along from one cliff-hanging chapter to the next. City at World’s End is nobody’s idea of fine literature, of course, but pulp sci-fi surely doesn’t get too much better. The author makes some flubs here and there (for example, Varn is initially described as being “tall and lithe”; 50 pages later, she is a “prim little figure”), but most readers will never notice or even care, as Hamilton whisks them breathlessly along. Maybe not with the force of a “super atomic” tearing through the time-space continuum, but pretty powerfully, still… (Sandy Ferber, Fantasy Literature)

Comments

Post a Comment