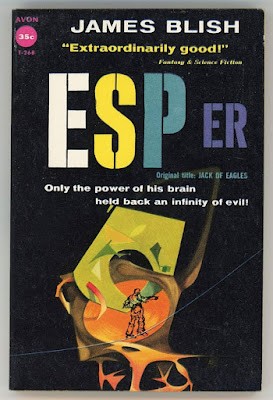

"ESPer" aka "Jack of Eagles" by James Blish

This is a most peculiar book, written by the prolific James Blish in 1952, better known to most SciFi readers for the 'Cities in Flight' and 'After Such Knowledge' series as well as being the author of a run of twelve early Star Trek novels. It was his first full novel.

Peculiar because it spends the first third or more as a standard pulp novel, even if it is above average in terms of its writing, about a G.I. Bill journalist who discovers his psy abilities. This gets him into a series of pickles that seem to culminate in a tale of gangsters and an FBI investigation.

Then it suddenly switches tempo into something entirely different yet still coherently linked with the tale told before ... gritty newsroom realism morphs in stages into occult conspiracy and a cosmic fantasy that would do credit to Kuttner (to whom he dedicates the book) and Moore.

What is remarkable though is that this is no cosmic space opera in the conventional sense. It is an attempt at hard science fiction but directed at the world of parapsychology and with an apparently masterful understanding of the mathematics and deep physics of the time.

I say, apparently, because as a tale of distorted space and time and of paranoid conflict between an evil and manipulative occultist secret society and self-sacrificing scientific heroes who have mastered psi abilities to ever greater levels, this is 'Doctor Strange' on speed.

Although the science is definitely obscure (one assumes it is intended to be so), it does not feel wholly implausible so it is still reasonable to see this as hard science fiction exploring occult and esoteric themes rather than as esoteric or occult pulp.

Over a decade before the Marvel magician's appearance (1963), Blish attempts to demonstrate that the esoteric and occult are no more than yet-to-be understood science with as much potential and danger as space travel or atoms. It tries to go below the level of the atom into the quantum world.

Arthur C. Clarke's pronunciamento on any sufficiently advanced technology being indistinguishable from magic was also made only in 1962 so this novel is a light-hearted pulp precursor to two iconic expressions of the same basic thought - that magic is ultimately science.

Once you get past the gangsters, it is a consistently entertaining but still not a great novel, partly because Blish, clearly a highly intelligent author, is showing off with his hard physics without always being clear enough about it to leave us without the impression that he is bluffing.

The novel never entirely leaves behind the jocular sub-hard-boiled tone of the first third so that what could be a 'serious' imaginative exploration of the implications of quantum physics and its relation to the occult/esoteric is lost in what becomes a jape, albeit a very stimulating one.

This is not to say that Blish fails at all in his most Kuttnerian moments. The story moves fast and there are some remarkable scenes as Danny Caiden, the clearly very bright hero, moves from cosmic sequence to cosmic sequence into alternate realities engineered by the bad guys.

Blish makes considerable effort to dismiss occult charlatanism. It is clear early on that, through the researches of the character of Caiden, he was himself both well read in and fascinated by occult lore and yet always remained determinedly rationalist and scientific in his prejudices.

I can imagine Blish saying, in the words of my son when he was younger pondering his love for imaginative popular culture, "I know none of it is true but I wish it was". So what does Blish do - he makes it (the occult) true through science and so preserves his natural rational outlook on life.

The 'bad guys' are marked out not only by their evil intentions but by the fact that they seem really to believe that they are working with merely occult forces. The 'good guys' operate at a higher level having mastered a technology based on a science that then explains what appears to be 'occult'.

If 'occult' means 'hidden', the 'good guys' (practical parapsychologists with the latent powers in humanity now fully expressed and aware of how psi can be as dangerous as the atom) may keep their knowledge hidden from the rest of humanity but it is no longer hidden to science.

Blish would remain fascinated by occult and religio-mythic themes, as evidenced by the 'After Such Knowledge' sequence. One wonders what sort of dialectic there was between him and Arthur C. Clarke where one detects some similarities of interest despite great differences in tone.

Clarke's original version of 'Childhood's end' was initially published in America with an unauthorised different ending by Blish in 1950. Clarke's story included themes of clairvoyance and telekinesis which emerge also in Blish's novel and it has scientific 'demons' as in 'Black Easter'.

If you do decide to read it, I have some recommendations - persevere through the first third or so and just enjoy it as well written pulp and then switch mentality in the second two thirds, do not allow yourself to be boondoggled by the 'hard science' and just enjoy the Kuttnerian cosmicism. (Tim Pendry, Goodreads)

Comments

Post a Comment